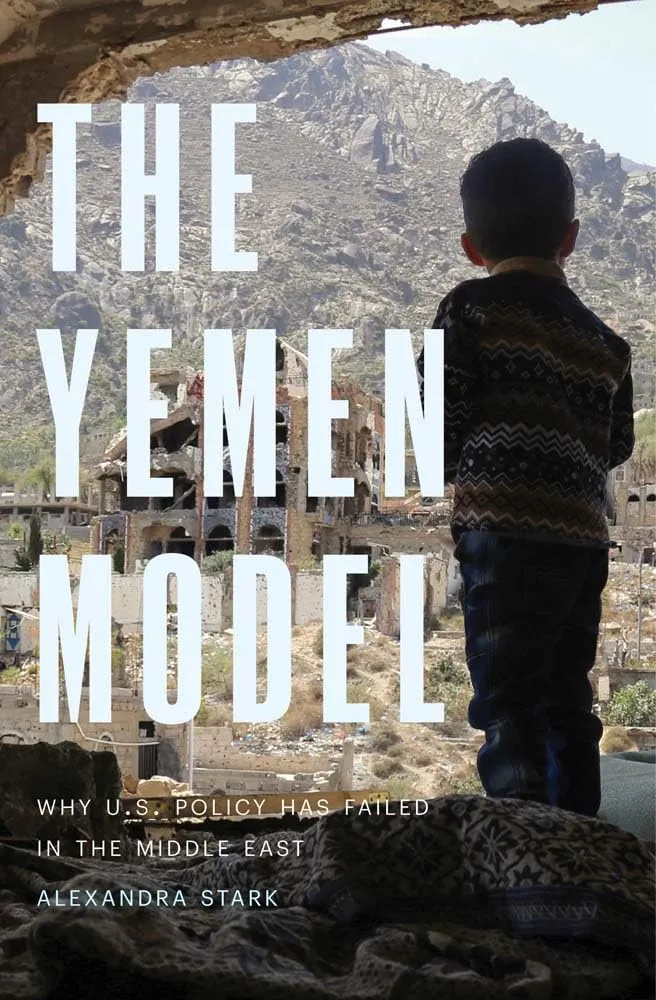

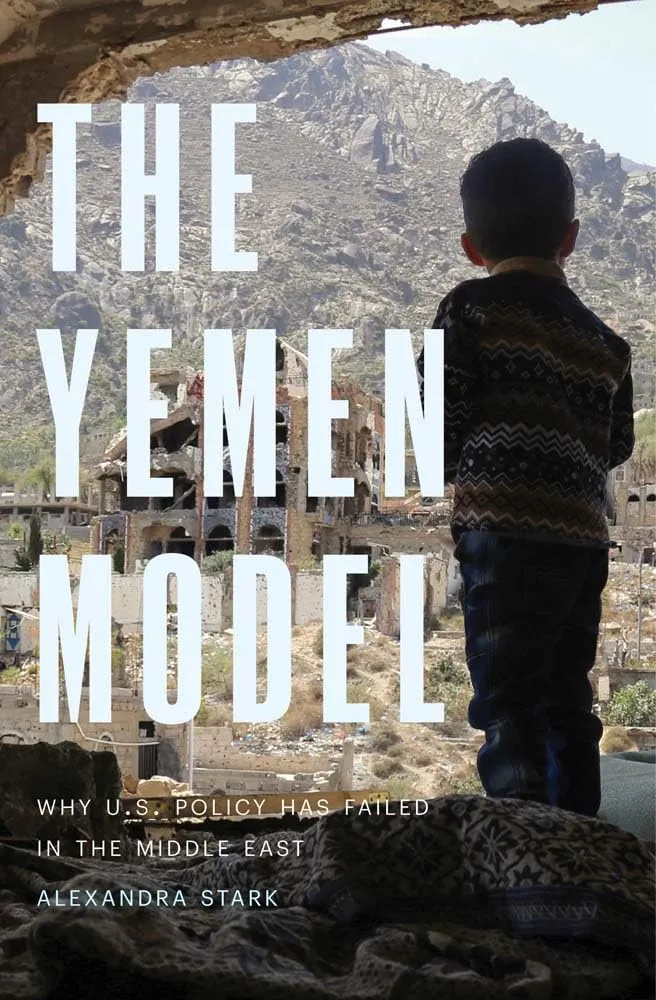

The Yemen Model: Why US Policy Failed in the Middle East

Alexandra Stark

November 7, 2025

Reviewed By

Arooba Younas

Reviewed By

The Yemen Model: Why US Policy Has Failed in the Middle East by Alexandra Stark is a historical account of Yemen and the United States’ failure to achieve its regional security ends and policy goals in the southern Arabian country. Using the US’s engagement in Yemen as a case study, Stark offers a range of lessons that the US can learn to effectively revise its policy in the Middle East more broadly. Furthermore, she argues that American foreign policy has failed because it was confined to counterterrorism and aiding regional security partners to contain Iran and the Houthis.

This book was authored to understand the US involvement in Yemen despite President Obama’s stern opposition to “dumb wars” and his presidential campaign to shrink the US military presence in the Middle East. Alexandra Stark is an associate political scientist at RAND and previously served as a senior researcher at the New America Future Security Programme. This book is a portrayal of her expertise in civil wars and irregular warfare.

In this book, Stark provides detailed insight into the history of Yemen, from British colonisation to its existence as two independent states, namely North and South Yemen, in the 1960s, and its functioning as a unified polity from 1990 to 2014. She further explores the Yemeni civil and proxy wars, along with the waves of insurgency that have marked the country’s history.

These conflicts were often shaped by external interventions aimed at asserting regional hegemony and safeguarding political and national security interests. While peace was occasionally negotiated, it remained short-lived as the underlying grievances were not addressed. For example, under Saleh’s regime in unified Yemen, the South was aggrieved because the central government siphoned off revenues from its petroleum production to oil the wheels of its patronage system. This led to the birth of al-Hirak al-Janoubi as a manifestation of the South’s resentment of the North’s political dominance.

The book situates the US counterterrorism operations in Yemen within the context of the Global War on Terror. It highlights the use of the “Yemen Model” to target al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). This was a lighter-footprint approach that did not require American troops on foreign soil. It was characterised as “intelligence-driven, dynamic targeting” that involved partnerships with local government forces and the use of air and drone strikes.

Stark identifies the failure of the flawed Yemen Model based on two factors. Firstly, the US extended support to autocratic leaders and political elites who had vested interests in becoming partners with Washington. The Yemeni administration of President Saleh welcomed the flow of US military aid because it helped serve the political interests of the elites. Therefore, Saleh’s government was prone to working against US interests of eradicating AQAP through lax counterterrorism missions to maintain the aid flow.

This was evident in the opposition of Saleh’s government when funding shifted from counterterrorism to democracy promotion. Subsequently, twenty-three AQAP militants escaped from a Yemeni prison with the help of security officials. Secondly, the hands-off approach led the US to view Yemen exclusively through a counterterrorism lens, focusing narrowly on achieving short-term tactical goals. This approach overlooked deeper structural issues of poor governance and corruption, which played a significant role in the rise of terrorist groups.

Stark’s work is not theoretically grounded in a way that would lend further credence and value to her book. For example, the neoclassical theory of overbalancing offers a cogent explanation for the Saudi-led coalition’s involvement in Yemen, rooted in Saudi Arabia’s insecurity over the perceived threat posed by the Iran-aligned Houthis advancing to its southern border. This situation was interpreted as a strategic encirclement by Saudi elites that led to a disproportionately strong reaction, exceeding the actual threat posed by the Houthis.

Although Stark acknowledges that local voices have been overshadowed by academia’s parochial outlook due to its narrow focus on the US role in the Middle East, her own analysis also falls prey to this myopic representation. Her work glaringly lacks the Yemeni perspective on US counterterrorism operations and external interventions in their homeland. This is because her data collection remained limited to US-based interviews, including former officials, congressional staffers, and advocates. Therefore, the book is predominantly narrated from a US perspective, occasionally referencing historical events such as the Arab Spring to contextualise the 2015 intervention by the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen.

An unequivocal statement is missing. Within US foreign policy, Yemenis are seen as targets — either active combatants or unfortunate collateral damage. Therefore, Yemen headlines the news only when the interests of the US and its allies are thwarted. This augments the assertion that Yemen has always remained a footnote because the corridors of power do not place any value on Yemeni lives; rather, they prioritise gaining regional political leverage with a blatant disregard for Yemeni lives.

Yet, Stark mentions that one of the motivations for US engagement with the coalition was to impose limits on its behaviour. However, despite this, she maintains an apologetic stance towards the US approach by making it seem as though the fault lies solely with the Saudi-led coalition for causing civilian deaths, as they did not meet the “standards” that the US pushed for them to uphold.

Although ineffective, the US counterterrorism approach excessively relied on airpower. To that effect, Stark mentions the operational training and targeting support provided by the US Department of Defence to the coalition’s pilots, though the details are missing. Additionally, although drone warfare achieved tactical success as part of the Yemen Model, it did more harm than good. The collateral damage associated with drones made recruitment for AQAP easier, as otherwise neutral Yemenis became embittered. Consequently, drones severely undermined the strategic goals of US counterterrorism efforts and national security objectives.

Towards the end, Stark outlines lessons for the US to learn from its engagement in Yemen. In her portrayal, however, the US is the only feasible force that can help reach a political solution in Yemen, overlooking other actors that could play a significant role. This is despite her acknowledgement that US choices have caused errors and incremental harms.

The role of China in the region, especially in her chapter detailing recommendations, is not mentioned, making her work US-centric. This is significant given Chinese interest in regional power projection, making the preservation of political stability its primary objective. Additionally, Beijing’s relationship with multiple powers in the region can allow it to facilitate dialogue — the Saudi-Iran détente being a demonstration of China’s diplomatic capability.

While urging the US to rethink its approach to counterterrorism, Stark does not acknowledge the reality of Yemen as a predatory state running on elite capture, subsequently turning into a “chaos state” that does not conform to the Westphalian model of the state. This comes with the assumption that the presence of a strong central government and institutions can implement policies in a top-down pattern.

The reality of predatory leadership that prioritises resource extraction over public goods provision causes underinvestment in critical areas, strengthening corruption, weakening institutions, and perpetuating cycles of exploitation. Ultimately, the state becomes incapable of addressing the needs of the citizenry, causing frustration within the population. The disengagement from this reality has led external actors to fail to appreciate the political and economic ecology of the state, which operates on improvised systems of government, trade, and politics, where Yemeni citizens find ways to live despite horrific circumstances.

To conclude, The Yemen Model: Why US Policy Has Failed in the Middle East is a comprehensive primer for understanding the convoluted situation in Yemen, particularly for readers unfamiliar with the country. In plain language, Stark divides her book into two parts: one delineating the history of the region to contextualise Yemen’s civil war, and the second examining the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations to understand the evolution of US policy in Yemen, alongside the role of Congress and American advocacy.

However, the focus on the US perspective skews her analysis, sidelining the Yemeni point of view that would be vital in guiding US actions in the country. Nevertheless, the book remains a valuable addition to Middle Eastern discourse, particularly due to its focus on Yemen, a country long viewed merely as a means to a security end.

The Centre for Aerospace & Security Studies (CASS) was established in July 2021 to inform policymakers and the public about issues related to aerospace and security from an independent, non-partisan and future-centric analytical lens.

@2025 – All Right Reserved with CASS Lahore.