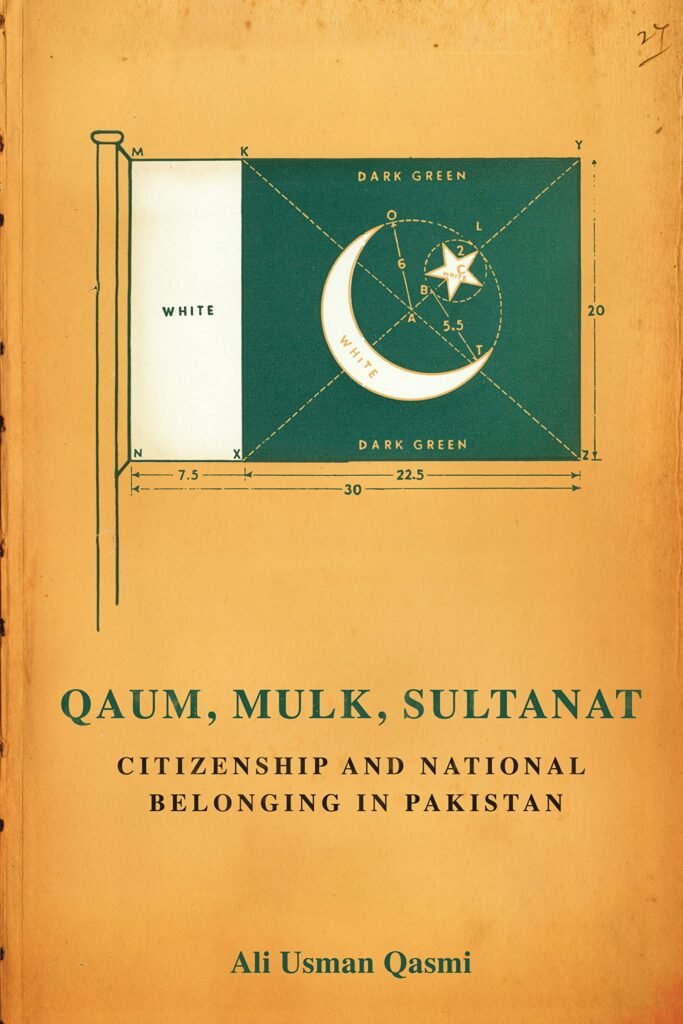

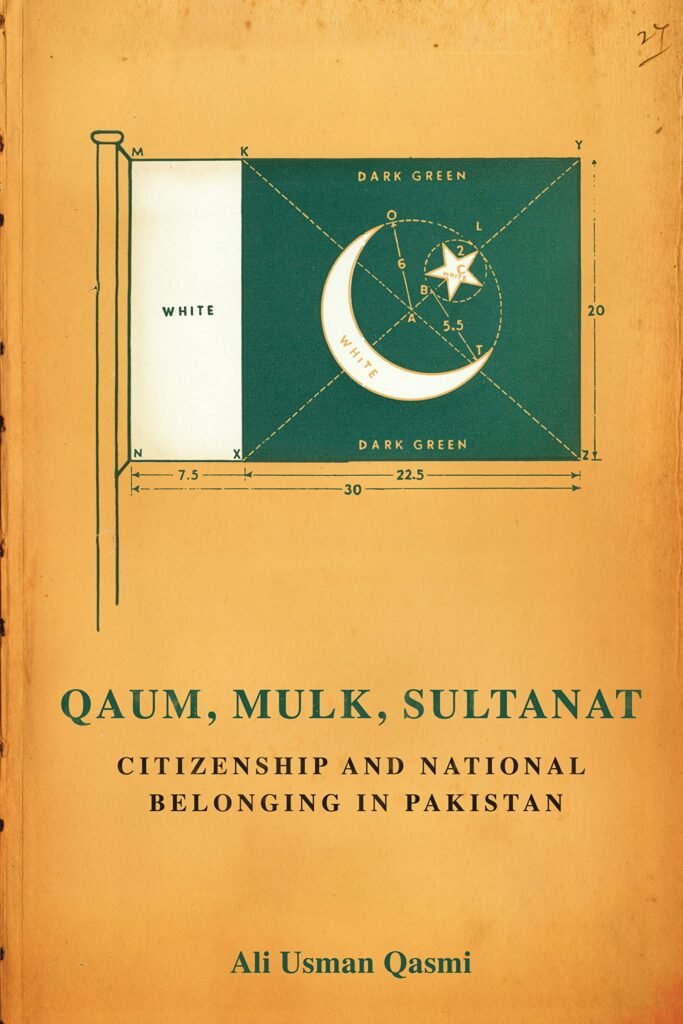

Qaum, Mulk, Sultanat: Citizenship and National Belonging in Pakistan

Ali Usman Qasmi

March 7, 2025

Reviewed By

Azhar Zeeshan

Reviewed By

Pakistan’s history in general, and particularly the process of its identity formation after its have long captivated the attention of academics and scholars. This enduring interest has resulted in a significant corpus of literature examining various aspects of the country’s national identity. Despite the extensive scholarship on this subject, Ali Usman Qasmi’s recent book Qaum, Mulk, Sultanat: Citizenship and National Belonging in Pakistan, offers a nuanced theoretical exploration of the process of the construction of national identity in Pakistan.

Dr. Ali Usman Qasmi is an Associate Professor of History at Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS). He is widely recognised for his extensive scholarship on the intersection of Islam, state, and society in Pakistan. He has authored and edited several acclaimed books including The Ahmadis and the Politics of Religious Exclusion in Pakistan, and Muslims against the Muslim League: Critiques of the Ideas of Pakistan. This robust academic background and reputation for meticulous research on Pakistan’s history establish him as a credible authority on the subject addressed in Qaum, Mulk, Sultanat.

In the introductory section of the book, Qasmi introduces the readers to the concept of citizenship and how it is different from nationality which is roughly translated as “Qaum” in the context of Pakistan. According to Qasmi, citizenship in simple words refers to the process of “designating who is a legal member of a political community”. However, he adds that in the case of Pakistan, it is not simply a legal process, as the bureaucracy that issues the papers to ‘designate’ a citizen has an ideology of belonging that transformed this legal process into an ideological enterprise. While explaining all these things, Qasmi draws upon a substantial body of theoretical literature, some of it in rather inaccessible language as theories often tend to be, and also provided several cases of people desiring a certain citizenship and being either granted or denied it.

In the subsequent chapters of the book, the author shifts his focus towards the process of identity formation in Pakistan since 1947 in which he specifically examines the role of Islam in it. Qasmi does so by going through the debates of legislative assembly in 1950 in which he highlights how ulema and modernist or moderate politicians clashed over interpretations of Islam’s role in governance. According to Qasmi, while ulema were advocating for an ideological state at the expense of non-Muslims and restricting women’s roles, modernists pushed back against these regressive tendencies.

In the concluding sections of the book, Qasmi examines the national symbols like the national flag, anthem, and calendar, which, according to him, were meticulously crafted in the framework of Islam to unify the nation in the name of religion and to distinguish it from “Hindu India.” To further strengthen his argument, Qasmi also provide details of how Pakistan’s archives, road names, and museums were shaped to present an Islamic and anti-colonial identity and narrative. In this regard, the author provides an interesting example of how Mughal artifacts were claimed as Pakistan’s heritage, while Hindu and colonial remnants were systematically erased. Through these details, Qasmi reveals the state’s obsession with crafting a single Islamic national identity that would counterbalance ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity in the country.

When it comes to the positives of the book, the most appreciating aspect is its foundation in extensive archival research which is deemed very valuable in the field of history. Just to provide an example, Qasmi’s whole discussion of the Pakistan Citizenship Law of 1951 in the book is heavily based on data from the National Archives of Pakistan, which includes but not limited to reports, notifications, and summaries from various ministries at that time. Thus, this reliance on archival data, much of which has not been previously accessed makes the book a significant contribution.

But this is not to imply that the book is without any downside. One of the notable downsides of the book is that is is written in a complex language which may not be accessible to a broader audience. For instance, the language employed throughout the text often leans heavily on complex theoretical and academic jargons which may alienate readers without a strong academic background in political science, international relations, or history. This limitation might narrow the potential readership of an otherwise important book.

Overall, in the opinion of this reviewer, the book, in the wake of its combination of theoretical rigor and empirical depth, is an important read to understand how Pakistan’s state, citizens, ulema, and intellectuals have imagined, narrated and formed Pakistan’s identity. The book is recommended for those who are interested in postcolonial state making in general and in Pakistan’s postcolonial history specifically. As mentioned above, those with no background in political science, history, or international relations may find it challenging, however, it would be a challenge worth undertaking.

The Centre for Aerospace & Security Studies (CASS) was established in July 2021 to inform policymakers and the public about issues related to aerospace and security from an independent, non-partisan and future-centric analytical lens.

@2025 – All Right Reserved with CASS Lahore.