BVR Mastery and MDO Precision: A Real Account of the May 2025 Air Battle

Ameer Abdullah Khan

19 November 2025

We are living in the age of infodemic, where information mixed with disinformation and misinformation spreads like a pandemic. A plethora of literature has been produced on the largest Beyond Visual range (BVR) air battle between the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) and the Indian Air Force (IAF) in early May 2025. Every author has attempted to explain the conflict from their own perspective and political standpoint. However, victories speak for themselves, and the PAF’s success was so undeniable that no one, including the US President and the usually biased Western media, could deny it. Nevertheless, several flawed interpretations of the PAF’s victory are plaguing the body of knowledge.

The Economist’s recent article, “How did Pakistan shoot down India’s fighter jets?” by Akalia Kalan, is among the hundreds of such pieces that claim to be investigative and analytical studies but, in essence, try to camouflage the IAF’s defeat. The article is representative of the literature, based on four flawed assumptions which distort the operational realities of the conflict. These narratives also attempt to appease and provide the IAF with a face-saving, but fail to appreciate the doctrinal transformation within the PAF. Lastly, such literature also exaggerates India’s retaliatory effectiveness. This piece, grounded in the lexicon and praxis of air warfare, aims to debunk these myths and respond to the propaganda narratives.

The first assumption worthy of scrutiny is the claim that India’s loss of seven fighter aircraft was the result of its political restraint. Echoing the narrative of Indian security officials and their media, the article claims that due to the political directive for the IAF not to engage Pakistani military installations, Indian jets were not equipped with air-to-air missiles. Resultantly, the IAF was not prepared to defend itself against the PAF ambush and found itself tactically outmanoeuvred and publicly embarrassed on the first night of the conflict.

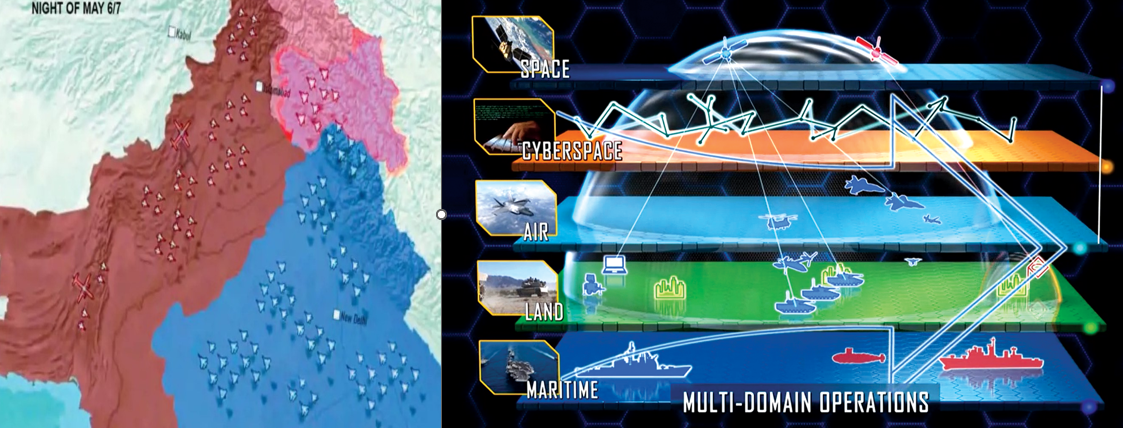

This hypothesis is not only doctrinally untenable but may also sound like a comedy to any student of air power. The Offensive Counter Air (OCA) missions, by definition, are aggressive and pre-emptive. These missions are designed with the expectation of retaliation and demand comprehensive adversary response modelling. OCA missions are structured around multi-layered air packages consisting of dedicated strike platforms, escort fighters armed with air-to-air missiles, suppression of enemy air defences (SEAD) platforms, airborne early warning and control systems (AEW&C), electronic warfare (EW) assets, and air-to-air refuelling tankers. Designed to achieve penetration, destruction, and survivability in contested airspace, these elements operate within a tightly synchronised kill chain. Therefore, the claim that Indian Rafales were dispatched without Meteor beyond-visual-range air-to-air missiles or sufficient EW support strains credulity and contradicts the fundamental tenets of air operations planning. Moreover, considering the IAF’s deployment of over 75 aircraft on the night of 6 and 7 May, it is implausible that none were equipped with the requisite weaponry.

It is also pertinent to note that this BVR aerial combat was not a sudden, unplanned engagement but rather occurred in an environment of heightened military readiness on both sides. Soon after the false-flag Pahalgam attack, both air forces expanded Combat Air Patrols (CAPs) and enhanced electronic surveillance. Most importantly, in the days leading up to the conflict, PAF jammed the radar systems of four Indian Rafale fighters. This successful non-kinetic manoeuvre forced the IAF Rafales to make an emergency landing and delivered a preview of the PAF’s latent might in the electromagnetic spectrum. Thus, to suggest that a professional air force like the IAF initiated an offensive under the assumption of a non-retaliatory response is operationally naive and borders on absurdity. Such an assumption, if true, would constitute a catastrophic failure in strategic intelligence and mission planning, not a noble act of political restraint.

Any postulation that the adversary would not respond, especially in a theatre historically marked by high-alert postures and rapid mobilisation cycles, reveals either a severe lapse in mission planning or a deliberate underestimation of the PAF’s capabilities. Even at the tactical level, junior officers are trained to model enemy reactions through red teaming and contingency drills. Thus, the IAF’s loss of seven aircraft on the first night must be examined through the lens of operational design failure, not merely political inhibition.

The second assumption — that the IAF was caught off guard due to inadequate mission data or limitations in its electronic warfare architecture — also requires critical examination. The Rafale, equipped with the SPECTRA electronic warfare suite, was procured precisely to address the EW deficiencies exposed during the 2019 Balakot episode. If the Rafale’s Spectra EW suite failed to counter PL-15 engagements, the failure lies not in the absence of equipment but in the inadequacy of mission-specific electronic order of battle (EOB) programming and electronic intelligence (ELINT) preparation. The inability to tailor the SPECTRA suite’s threat libraries or integrate it with India’s airborne platforms, such as the NETRA AEW&C or the Su-30MKI, suggests institutional inertia, interoperability failure, and systems integration gaps, rather than an inherent technological deficiency. Moreover, the accusations that Dassault’s refusal to share source code hindered Indian operational effectiveness only underscore longstanding issues in India’s defence acquisition ecosystem, where platform procurement often outpaces doctrinal assimilation and indigenous operational tailoring.

The third flawed proposition is that the technological superiority of Chinese-supplied platforms was the sole determinant of the PAF’s success. While the operational debut of the J-10C fighter and the PL-15E long-range air-to-air missile certainly enhanced Pakistan’s aerial strike envelope, the decisive edge did not stem from hardware alone. Real-time data sharing and sensor fusion are standard practices in modern warfare, particularly among strategic allies and partners. However, this reality should not obscure the fact that Pakistan entirely relied on its indigenous resources during the whole conflict. The difference in this instance was the PAF’s ability to internalise and operationalise Chinese equipment through joint command structures and war-gamed contingency planning. The 2025 conflict marked the culmination of a doctrinal shift within the PAF under the leadership of Air Chief Marshal (ACM) Zaheer Ahmad Baber Sidhu. During the past four years, the PAF has transformed from a platform-centric force to one guided by effects-based operations.

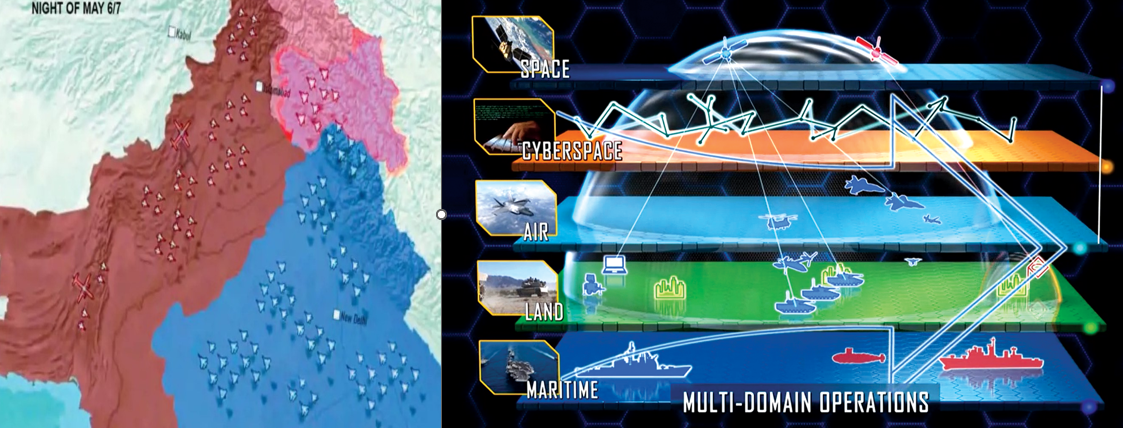

What unfolded during the conflict was a textbook execution of Multi-Domain Operations (MDO), in which PAF synchronised capabilities across the space, cyber, electronic, and air domains to establish a seamless kill chain. Space-based intelligence, cyber denial of adversary networks, precision-guided kinetic strikes, and real-time ISR (intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance) fusion coalesced into an integrated battle network. This network-centric approach enabled the PAF to detect, fix, track, and neutralise IAF targets with lethal precision and minimal latency. It is no secret that the PAF had pre-scripted scenarios that anticipated Indian aggression and rehearsed integrated response options during multiple air defence exercises and command post simulations. Thus, it was not Chinese equipment that won the night, but rather how these tools were deployed into a coherent and adaptive doctrine.

Lastly, Western and Indian discourse perpetuates the myth of the success of Indian hypersonic missile strikes against some Pakistani targets as evidence of regained dominance and operational success. Such claims lack nuance and analytical depth in terms of deterrence posture and aerial engagement doctrine, given that Pakistan does not possess a missile defence shield akin to Israel’s Iron Dome or Russia’s S-400. Pakistan’s deterrent posture is primarily based on an offensive counter-strike capability and survivability through dispersion and redundancy. Penetrating a lightly defended infrastructure with hypersonic stand-off weapons with minimum precision is not a demonstration of air superiority but a reflection of strategic asymmetry. What is notable, however, is that Pakistan successfully executed soft kills against incoming hypersonic missiles through its indigenous systems. This is an operational feat rarely achieved even by advanced militaries, as evident from Israel’s helplessness against Iranian missile strikes. The PAF made these interceptions possible through indigenously developed advanced electronic counter-countermeasures (ECCM) and terminal deception technologies, marking a new threshold in regional air defence capability.

Most of the literature perpetuating these myths originates from the West, reflecting the anxieties of the Western military-industrial complex. Such narratives subtly seek to deflect scrutiny from the performance of Western platforms, particularly Dassault Aviation, which is consistently under pressure to reassure existing and prospective clients about the effectiveness of its systems. It also reflects the West’s eagerness to appease the Indian Air Force, considering its significant purchases, particularly the Medium Multi-Role Combat Aircraft (MMRCA) 2.0 tender. Furthermore, the recent statement by the Indian Chief of Defence Staff, claiming that today’s wars cannot be won with yesterday’s weapons, also illustrates India’s desire for more lavish defence procurements offering business opportunities to the West. In parallel, through such claims, the effectiveness of China’s military technology is being exaggerated to suit the West’s narrative of a rising China as a threat to its dominance.

Such narratives, while apparently grounded in factual reporting and independent analyses, deliberately overlook the conflict’s doctrinal, operational, and strategic layers. PAF, spearheaded by ACM Sidhu, has demonstrated its successful transition into a next-generation thinking force, leveraging information dominance, operational integration, and doctrinal foresight to neutralise a numerically superior and egoistic competitor. In attempting to rationalise the IAF’s underperformance through political, technological, and procedural caveats, most Western literature fails to acknowledge the most critical variable: the PAF’s ability to think, plan, and fight as a modern air force. The 2025 engagement was not a contest of equipment, but rather a contest of doctrine, preparation, and execution, and in this contest, the Pakistan Air Force prevailed.

The Centre for Aerospace & Security Studies (CASS) was established in July 2021 to inform policymakers and the public about issues related to aerospace and security from an independent, non-partisan and future-centric analytical lens.

@2025 – All Right Reserved with CASS Lahore.