Gulf labour reforms and Pakistan’s remittance risk

Amjad Fraz

07 August 2025

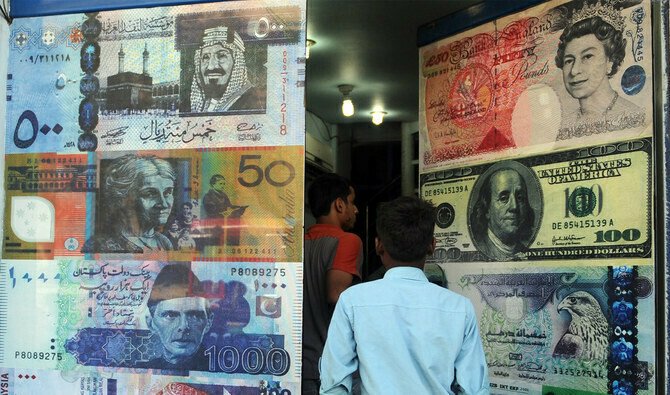

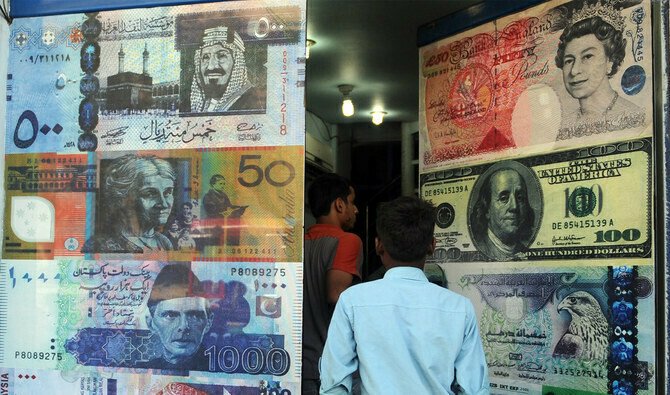

Overseas Pakistanis sustain the economy in ways that exports, bailout packages, and short-term borrowing cannot. In FY 2024-25, workers sent home a record USD 38.3 billion, a sum equivalent to one per cent of national output and sufficient to cover every cent of the USD 26.3-billion trade deficit that same year. This is the product of over nine million Pakistani migrants employed abroad, particularly in the Gulf. However, recent localisation quotas and skill-tier visa rules in the Gulf threaten to choke this lifeline.

State Bank data confirms the scale of remittance dependence. Two Gulf monarchies supplied almost half of that sum: the KSA sent USD 9.3 billion and the UAE added USD 7.9 billion. The four remaining members of the GCC lifted the regional total to USD 18.7 billion. By contrast, the UK and the US together accounted for USD 10.5 billion. The arithmetic is simple. Every second remittance dollar comes from the Gulf.

The people generating the flow are equally concentrated. During the first half of 2025, the Bureau of Emigration cleared 336,999 Pakistanis for foreign employment. Two out of three were bound for KSA, while fewer than 14,000 secured posts in the Emirates. While only three per cent were professionals, nine in ten travelled as general labourers. Despite occupying the lowest rungs of the Gulf labour ladder, each newcomer remits about 6500 dollars during the first year abroad. Multiply that modest figure by the hundreds of thousands who leave annually, and the impact on Pakistan’s current account becomes immediate and profound.

This pipeline was built during a different economic climate. The last decade’s oil-fuelled construction plans drove Riyadh and Abu Dhabi to issue “block visas” to workforce agencies. Contractors could secure visas for Pakistani labour within days. This exodus supported reserves whenever export receipts faltered. Families grew used to the rhythm of monthly transfers, while the federal budget silently benefited from foreign exchange it did not have to borrow.

The rhythm is changing. Gulf governments now face domestic pressure to place their citizens in private-sector jobs. The UAE extended its Emiratisation quota at the start of 2024 to firms with as few as twenty employees. Businesses that miss the target pay fines that rise from 96000 dirhams per vacancy in the first year to 108000 dirhams in the second. Saudi Arabia broadened its Saudisation programme even further. In May 2025, the kingdom froze “block visa” issuance for fourteen nationalities, Pakistan included. One month earlier, it had imposed localisation ratios of up to seventy per cent in key health-care roles. Both measures narrow exactly those entry points that tens of thousands of Pakistani workers have relied on for decades.

If the new rules reduce fresh placements by just fifteen per cent in 2026, around one hundred thousand departures will disappear. At current earning patterns, a twenty per cent contraction would cost more than one billion dollars, equivalent to one tenth of the annual petroleum import bill. The timing could scarcely be worse. External debt service is projected to exceed twenty-five billion dollars in the 2026 financial year, the heaviest annual burden in Pakistan’s history. Smaller inflows, heavier outflows, and a thin reserve cushion would place renewed pressure on the rupee and household prices.

The shock would also echo through the domestic labour market. Those 100,000 migrants who never leave, or who return early after failing the visa renewal, will seek work in construction, transport, and retail sectors that have expanded by less than three per cent a year since 2023. Urban unemployment could rise by half a percentage point, while provincial welfare budgets, already stretched by a twenty-seven per cent increase this year, would face fresh demand.

Labour-exporting countries are adjusting to stricter Gulf rules. Bangladesh mandates Saudi Skills Verification for thirty-three trades, opening test centres that certify workers before they lodge visas. The Philippines sends Technical Education and Skills Development Authority teams abroad to assess and upgrade migrants’ National Certificate for higher-tier visa eligibility. Pakistan also has room to manoeuvre, but it must act with clarity and speed.

Two steps can protect the remittance lifeline while respecting Gulf labour priorities. First, the National Vocational and Technical Training Commission should map high-demand trades, such as solar installation and geriatric nursing, to Saudi and Emirati assessment frameworks. Second, Islamabad should secure an annual package of positions for certified skilled individuals whose qualifications align with Saudi Vision 2030 and the Emirates’ clean-energy drive. Targeted visas would reward competence, not headcount. These measures are modest in cost yet large in effect. Certificate alignment relies on curriculum work already underway. A quota bargain trades skills for access, which both sides value.

In conclusion, remittances have kept shop lights burning, paid university fees, and softened the worst blows of inflation. Exporting muscles alone will no longer suffice. Exporting verified expertise can keep the money flowing, perhaps at an even higher rate per worker, while Gulf economies modernise.

The Centre for Aerospace & Security Studies (CASS) was established in July 2021 to inform policymakers and the public about issues related to aerospace and security from an independent, non-partisan and future-centric analytical lens.

@2025 – All Right Reserved with CASS Lahore.